ZEP 2 - Sharding codec

Authors:

- Jonathan Striebel (@jstriebel), scalable minds

- Norman Rzepka (@normanrz), scalable minds

- Jeremy Maitin-Shepard (@jbms), Google

Status: Accepted via zarr-developers/zarr-specs/#254

Type: Specification

Created: 2022-08-02

Accepted: 2023-11-01

This ZEP is accompanied by the sharding extension specification [SHARDINGSPEC].

Abstract

This ZEP proposes to add a sharding codec to the Zarr specification version 3. This permits combining multiple chunks into storage keys, enabling the usage of larger arrays with Zarr.

Motivation and Scope

Currently, Zarr maps one array chunk to one storage key. This becomes a bottleneck as storing large arrays usually requires a large number of chunks, which becomes inefficient or impractical to store when a chunk is mapped directly to files or objects in the underlying storage. For example, the file block size and maximum inode number restrict the usage of numerous small files for typical file systems, also cloud storage such as S3, GCS, and various distributed filesystems do not efficiently handle large numbers of small files or objects.

Increasing the chunk size works only up to a certain point, as chunk sizes need to be small for read and write efficiency requirements, for example to stream data in browser-based visualization software.

Therefore, chunks may need to be smaller than the minimum size of one storage key. In those cases, it is efficient to store objects at a more coarse granularity than reading chunks.

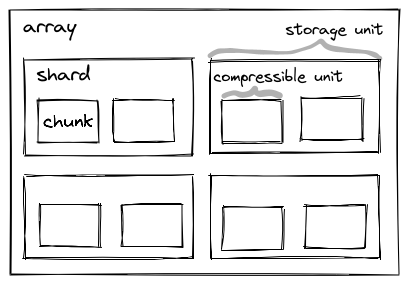

Sharding solves this by allowing to store multiple chunks in one storage key, which is called a shard:

The following example illustrates the need for sharding:

The dataset has a shape of (25000, 18000, 6000) and a dtype of uint8. This makes for a total size of 2.4TB. For efficient reads and fast streaming of the data, e.g. to a browser-based interface, chunk sizes should be of max. (64, 64, 64). For this dataset that would result in 10.3M chunks, and without sharding also to 10.3M files. Considering having multiple of these datasets, the number of files becomes impractical. With sharding, one could use (32, 32, 32) chunks per shard, so that each shard has a size of (2048, 2048, 2048) voxels. That would reduce the number of files to ~300 while maintaining a practical write granularity.

To allow interoperability between different stores and Zarr implementations, we propose to standardize sharding as a codec specification.

Usage and Impact

Sharding allows storing very large, chunked arrays, which currently would have inefficient access characteristics or might even be impossible to store as generic Zarr arrays.

Image datasets in the biomedical, geo-science, and general data-science communities are steadily growing. In recent years, peta-scale datasets have been made publicly available. Although peta-scale datasets are still infrequent, tera-scale datasets are acquired routinely and rapidly grow in size further.

Currently, these large-scale datasets are made available through tool-specific formats, such as neuroglancer-precomputed or webknossos-wrap, which support sharding. While the data is accessible and explorable in individual software tools, wider interoperability with other software tools is limited. Whereas it has been possible to convert smaller datasets to work in different tools, it becomes infeasible for large-scale datasets. The choice of tool-specific formats is in part a result of the lack of a standard format that makes storage and processing of very large datasets practical. Providing sharding in Zarr would allow Zarr to become the standard format also for tera- and peta-scale array data and future-proofing it as a standard for the requirements of growing data sizes in the scientific community.

Backward Compatibility

This ZEP introduces a Zarr extension for Zarr version 3. The sharding extension is optional for data producers, and only necessary when reading arrays that are written using the sharding extension. It corresponds to a minor version change in semantic versioning, adding functionality in a backward compatible manner.

As codecs are specified in the array metadata, Zarr clients without implementation for the sharding extension should infer that they are lacking support for the specific array, as all codecs are required, non-optional extensions.

Detailed description

Combining regular blocks of chunks in a shard

To add sharding to Zarr, data that was stored previously as separate objects must be combined. Different strategies can be considered when sharding array data, such as:

- sharding across single dimensions,

- sharding by regular n-dimensional blocks of data, and

- sharding random combinations of chunks via hashing.

All of those strategies only shard the array data and not the metadata, since the latter is not big enough to warrant sharding and also because the sharding configuration itself is stored in the metadata.

Strategy 2 is a strict super-set of strategy 1, as sharding across a single dimension can be produced by sharding with n-dimensional blocks where all blocks consist of single chunks except for the selected dimension.

Strategy 3 permits balancing loads better between shards than the other two strategies. Since all shards will often be served via the same underlying storage, load-balancing does not have a high priority in this use case.

This ZEP proposes to use strategy 2, using regular n-dimensional blocks of chunks as sharding units, as it combines multiple chunks that are close to each other. This has the benefit of co-locating data that is usually accessed together or in short succession.

Sharding as a codec extension

Sharding can be an optional addition to the current Zarr features, as it is primarily important for very large arrays. Therefore it should be added as an extension, which can enhance different Zarr implementations.

Implementing sharding as a codec logically subdivides a chunk into smaller chunks (“inner chunks”). This fits well with the codec abstractions that encode and decode chunks through various algorithms. With the introduction of nested codecs in the sharding configuration inner chunks may be encoded further.

Some implementation may want to optimize reading and writing of single inner chunk through partial reads and writes as described below. This can be implemented by adding information about the chunk selection to the codec’s API. The experimental zarrita implementation demonstrates this.

Potential alternatives

Sharding by combining different chunks can only be implemented in logical units operating after chunking and indexing are done. Therefore it could be implemented directly in the storage layer, but this could result in different sharding implementations between different stores and Zarr implementations, compromising the core Zarr benefit of interoperability.

Sharding could also be implemented as a storage transformer, which is a new concept introduced in Zarr v3. The mental model of sharding would then be to group co-located chunks into a larger storage unit. This is inverted from the codec model of subdividing chunks into sub-chunks. The codec model has some benefits in terms of composability. Other codecs may want to encode entire shards, e.g. to add metadata in the binary format. Sharding as a storage transformer would make these compositions more difficult.

Configuration

The following part is cited from the accompanying sharding extension specification [SHARDINGSPEC].

Sharding can be configured per array in the array metadata as follows:

{

"codecs": [

{

"name": "sharding_indexed"

"configuration": {

"chunk_shape": [32, 32],

"codecs": [

{

"name": "endian",

"configuration": {

"endian": "little",

}

},

{

"name": "gzip",

"configuration": {

"level": 1

}

}

],

"index_codecs": [

{

"name": "endian",

"configuration": {

"endian": "little",

}

},

{ "name": "crc32c"}

]

}

}

]

}

chunk_shape

An array of integers specifying the size of the inner chunks in a shard along each dimension of the outer array. The length of the chunk_shape array must match the number of dimensions of the outer chunk to which this sharding codec is applied, and the chunk size along each dimension must evenly divide the size of the outer chunk. For example, an inner chunk shape of [32, 2] with an outer chunk shape [64, 64] indicates that 64 chunks are combined in one shard, 2 along the first dimension, and for each of those 32 along the second dimension.

codecs

Specifies a list of codecs to be used for encoding and decoding inner chunks. The value must be an array of objects, as specified in the array metadata. The codecs member is required and MUST contain exactly one array -> bytes codec.

index_codecs

Specifies a list of codecs to be used for encoding and decoding shard index. The value must be an array of objects, as specified in the array metadata. The index_codecs member is required and needs to contain exactly one array -> bytes codec. Codecs that produce variable-sized encoded representation, such as compression codecs, MUST NOT be used for index codecs. It is RECOMMENDED to use a little-endian codec followed by a crc32c checksum as index codecs.

Definitions

- Shard is a chunk of the outer array that corresponds to one storage object. As described in this document, shards MAY have multiple inner chunks.

- Inner chunk is a chunk within the shard.

- Shard shape is the chunk shape of the outer array.

- Inner chunk shape is defined by the

chunk_shapeconfiguration of the codec. The inner chunk shape needs to have the same dimensions as the shard shape and the inner chunk shape along each dimension must evenly divide the size of the shard shape. - Chunks per shard is the element-wise division of the shard shape by the inner chunk shape.

Binary shard format

The following part is cited from the accompanying sharding extension specification [SHARDINGSPEC].

This is an array -> bytes codec.

In the sharding_indexed binary format, inner chunks are written successively in a shard, where unused space between them is allowed, followed by an index referencing them.

The index is an array with 64-bit unsigned integers with a shape that matches the chunks per shard tuple with an appended dimension of size 2. For example, given a shard shape of [128, 128] and chunk shape of [32, 32], there are [4, 4] inner chunks in a shard. The corresponding shard index has a shape of [4, 4, 2].

The index contains the offset and nbytes values for each inner chunk. The offset[i] specifies the byte offset within the shard at which the encoded representation of chunk i begins, and nbytes[i] specifies the encoded length in bytes.

Empty inner chunks are denoted by setting both offset and nbytes to 2^64 - 1. Empty inner chunks are interpreted as being filled with the fill value. The index always has the full shape of all possible inner chunks per shard, even if they extend beyond the array shape.

The index is placed at the end of the file and encoded into binary representations using the specified index codecs. The byte size of the index is determined by the number of inner chunks in the shard n, i.e. the product of chunks per shard, and the choice of index codecs.

For an example, consider a shard shape of [64, 64], an inner chunk shape of [32, 32] and an index codec combination of a little-endian codec followed by a crc32c checksum codec. The size of the corresponding index is 16 (2x uint64) * 4 (chunks per shard) + 4 (crc32c checksum) = 68 bytes. The index would look like::

| chunk (0, 0) | chunk (0, 1) | chunk (1, 0) | chunk (1, 1) | |

| offset | nbytes | offset | nbytes | offset | nbytes | offset | nbytes | checksum |

| uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint64 | uint32 |

The actual order of the chunk content is not fixed and may be chosen by the implementation. All possible write orders are valid according to this specification and therefore can be read by any other implementation. When writing partial inner chunks into an existing shard, no specific order of the existing inner chunks may be expected. Some writing strategies might be

- Fixed order: Specify a fixed order (e.g. row-, column-major, or Morton order). When replacing existing inner chunks larger or equal-sized inner chunks may be replaced in-place, leaving unused space up to an upper limit that might possibly be specified. Please note that, for regular-sized uncompressed data, all inner chunks have the same size and can therefore be replaced in-place.

- Append-only: Any chunk to write is appended to the existing shard, followed by an updated index. If previous inner chunks are updated, their storage space becomes unused, as well as the previous index. This might be useful for storage that only allows append-only updates.

- Other formats: Other formats that accept additional bytes at the end of the file (such as HDF) could be used for storing shards, by writing the inner chunks in the order the format prescribes and appending a binary index derived from the byte offsets and lengths at the end of the file.

Any configuration parameters for the write strategy must not be part of the metadata document; instead they need to be configured at runtime, as this is implementation specific.

New CRC32C checksum codec

This ZEP introduces a new codec that appends CRC32C checksums to a bytestream. It is recommended to use this checksum codec for the shard index. It is a bytes -> bytes codec. The configuration and algorithm is described in the codec specification [CRC32CSPEC].

Use-cases and access strategies

Reading data per chunk

Reading single chunks can be done in two ways, depending on the capabilities of the underlying storage:

-

- Downloading the complete corresponding shard,

- reading the index and

- afterwards reading the relevant chunk.

-

- Downloading only the index of the corresponding shard,

- identifying the relevant byte-range for the requested chunk,

- only downloading this byte-range from the same shard.

The first method might especially be useful when caching not only the requested chunks but the whole shard, which will save bandwidth if subsequent chunk-requests are close to the previous chunks.

Storing a stream of data slices

Many image acquisition techniques produce slice-wise data, such as timeseries or z-slicing. This data can be written slice-wise using one of the following techniques:

- Using a chunk-size and shard-size of 1 for the sliced dimension effectively disables chunking and sharding for this dimension.

- Slice-wise data with a chunk-size of 1 for the sliced dimension can be appended to a shard, only wasting the space for the index that was written before.

- When using no compression, chunk-sizes are constant, and shard indices can be known ahead of time, allowing to write partial chunks of a shard. Therefore, a chunk-size of 1 can be used for the sliced dimension, in addition to a higher shard-size for this dimension. This is beneficial if later access typically consists of blocks with multiple slices.

- Strategy 3 can be combined with compression by writing the compressed chunks in the order they arrive, overwriting the old index and appending the updated index including the new chunks.

Updating chunks

Updating chunks can be done with different strategies, depending on the byte-length of the chunks and therefore depending on the compression:

- Uncompressed chunks can be rewritten in-place, since their size is constant and the index does not need to be updated.

- When updating compressed chunks one can also update the chunk in-place if there is enough unused space between the chunk and the following chunk (or index). However, the index must still be updated if the byte-length of the chunk changed.

- When the compressed chunk is larger than before and no unused space is available, it might either

- be appended to the shard, leaving the previous space unused, or

- rewriting the shard, moving also other chunks.

Related Work

- Neuroglancer precomputed format supports sharding

- webKnossos-wrap, blocks correspond to Zarr chunks, files to shards

- caterva, blocks correspond to Zarr chunks, caterva chunks to Zarr shards

- Apache Arrow supports data partitioning

- The following Zarr v2 sharded store implementation permits having virtual stores which are serialized into an underlying store: https://github.com/thewtex/shardedstore

Implementation

A Python implementation is drafted in the experimental zarrita implementation.

The following proof of concept implementations explored similar approaches:

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-python/pull/1111.

- https://github.com/alimanfoo/zarrita/pull/40

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-python/pull/876

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-python/pull/947

Discussion

- Review discussion:

- Previous discussions for the specification:

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-specs/issues/152

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-specs/issues/127

- https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-specs/pull/134

- Initial issue in

zarr-python:

- Other related discussions:

- https://forum.image.sc/t/ome-zarr-chunking-questions/66794

- https://forum.image.sc/t/sharding-support-in-ome-zarr/55409

- https://forum.image.sc/t/deciding-on-optimal-chunk-size/63023

- https://forum.image.sc/t/storing-large-ome-zarr-files-file-numbers-sharding-best-practices/70038

- https://github.com/thewtex/shardedstore/issues/17

References and Footnotes

-

[SHARDINGSPEC] - https://zarr-specs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/v3/codecs/sharding-indexed/v1.0.html

-

[CRC32CSPEC] - https://zarr-specs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/v3/codecs/crc32c/v1.0.html

License

To the extent possible under law, the authors have waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to ZEP 2.